It doesn’t take long for van de Sandt’s plot and writing to grip readers’ attention in this debut. Two timelines interweave around the circumstances of a single dinner party, set to celebrate the launch of Franca’s fiancé, Andrew’s, latest project, a canon of sorts inspired by time capsules. Franca once aspired to have a career, but it is clear that Andrew prefers a more domestic arrangement for her. Her father died while she was quite young, and her mother is distant, so her life with Andrew feels safe, initially. In his discussion with Franca over what should be served at the dinner party, Andrew throws off a mean vibe, even insisting that Franca get fresh rabbit to prepare, despite knowing she is a vegetarian. Kitchen disasters up the tension, and when one unexpected guest arrives, a friend of hers from Utrecht, the wrenching details of Franca’s relationship with Andrew are slowly revealed as the timeline shifts forward and back. Claustrophobic and thrilling at the same time, the book allows readers to follow Franca’s unwinding as she seeks revenge against the man who says he loves her, when he just wants to own her, body and soul. Readers will feel every bit of Franca’s female rage as she attempts to extricate herself from her untenable situation. At a time when “tradwife” movements are on the rise, which prioritize homemaking and caring for the husband, trusting him to provide and protect, this story is particularly relevant.

Book of the Week

Full-on brilliant, this sojourn into the groves of academe evolves into something totally dark and absolutely compelling. MFA grad David Trent is hanging around Cambridge cafes, reworking his novel for the umpteenth time, and lying to his fiance. It doesn’t help that his upstairs neighbor is Silas Hale, a renowned author who poses as a mentor when in fact he is nothing less than a monster who takes delight in torturing emerging authors (quite literally. In one of the funniest/most horrifying scenes, he refuses to supply David with any heat, despite it being winter in Boston.) But when David wins an award for his debut novel, everything changes, and even Silas is forced into welcoming his neighbor into the literary scene, albeit begrudgingly. From there, the novel, and David’s career, really take off. But enough from me. I refuse to let any of this devilishly satiric plot escape. Why take the fun away from other readers? Comparisons to Donna Tartt, Jean Hanff Korelitz, and Patricia Highsmith are inevitable. On my list of the top ten Best Books of 2025, this novel needs to be shared with a whole range of readers and enjoyed in book groups. They’ll be grateful.

Cordelia West lives a pretty simple life. A devoted young Dallas Public librarian, she likes to keep her past just that: in the past. This includes her mother, a former alcoholic, who pretty much wrecked her childhood (they’re now on better terms). But when she receives a letter from great-aunt Penelope—a relative she has never heard of—Cordelia can’t ignore it. She’s been named sole heir to Penelope’s estate back in their hometown of Sarsaparilla Falls, Texas, a place she has assiduously avoided the past few decades. Turns out her inheritance pretty much consists of the Chickadee Motel, which the will stipulates can’t be sold until all residents leave or pass away. So off she goes to Sarsaparilla to see how she can rid herself of these tenants. Cordelia is savvy, and soon after arriving, she figures out the motel is a brothel, with three over-60 sex workers—Daisy, Arline, and Belinda Sue—AKA the Chicks, all eager for Cordelia to sign on as madam. This is the backstory, which is absolutely delightful, but it’s just a launching pad for the rest of the novel, which features extortion, accidental murder, poisoning, blackmail, corrupt developers, a beguiling romantic subplot, and so much more. Lane has created a fascinating world populated with extraordinary characters. Here’s hoping we all meet again.

Therapist Sarah Newcomb can’t get her fiancé to commit to a wedding date. Still, doubts about their relationship take a back seat when one of her clients reveals evidence of a potential copycat killer. Newcomb uses past-life regression to help her clients overcome trauma, but this patient unveils a time in the future, and this part of their divided soul works as a homicide detective. Trying to prove her client is making up material, she learns from that split soul of a natural gas explosion that will kill seven people in New Mexico the next day. The following morning, federal agent Grant Lukather from Homeland Security visits a site in New Mexico where seven people died in a natural gas explosion. He learns of a 911 call that came in the day before, warning of the blast. Tracing the phone number puts him in Sarah’s office. The twists and turns that follow are wild and completely unpredictable, and the story only gets better as it becomes increasingly complex. Heisserer received an Oscar nomination for screenwriting for the film Arrival, and he delivers the cinematic scope and intensity of a novel-writing pro. And the ending! It’s hard to believe this is his first novel, and readers will eagerly want more.

Nikki Jackson-Ramanathan and her husband, Jai, live in a tiny apartment and get by on his job as a coach for a collegiate mock-trial team and her role as a dog walker and pet behaviorist. She’s asked by rich widow Ruth Van Meer to learn why her dog, Reginald, seems to be less energetic than usual. The rest of the Van Meer family appears petty and vindictive and question why Nikki was hired in the first place. Nikki begins to spend quality time with Reginald, taking him on walks every day, while the family continues to resent her presence. When Mrs. Van Meer is discovered deceased in her bed, the family begins pointing fingers at Nikki after it’s learned that the dead widow left a sizeable amount of money to Nikki to continue caring for Reginald. With the police’s dogged determination to prove Nikki’s guilt, and the eccentric family keeping her on a tight leash, she can’t let sleeping dogs lie and has to solve the murder herself. This engaging cast of quirky characters launches a terrific story that is hopefully the beginning of a series. Readers will also be wondering if Reginald is available to adopt.

It’s a big day for both Bridget Keller and her old family friend Jimmy Maguire. Jimmy’s being released from notorious English prison Wandsworth, having served decades for the murder of his childhood friend Providence. And Bridget, Providence’s older sister, is on her way to the prison gate to meet Jimmy and kill him. But things aren’t quite right for the attack, so Bridget puts it off…and puts it off…while she tails Jimmy as he visits old haunts, planning to kill him at every stop. As we journey with the ill-fated pair, readers look back at Bridget and Jimmy’s childhoods. Both have been abandoned by their mothers, Bridget physically when her mother took off, Jimmy emotionally as he survives life with his alcoholic mother; “the mister,” an abusive man whom Jimmy just KNOWS isn’t his father; and his small-time-criminal brothers. Nobody expects good from a Maguire. But as readers come to know Jimmy from his friendships, efforts to escape a life of crime, and sometimes-sparkling inner thoughts, it becomes harder to view him as just a criminal. Solid twists add to the emotional uncertainty to create a thought-provoking look at intersecting tough lives and longings for love.

“There will be no more diaries to fill, now.” How lonely, an emotion that echoes through this book that is sure to be on end-of-year best lists. It opens in present-day London and then flits back and forth between 1945 and present-day Paris, with an opulent city of lights hotel, the Lutetia, as the main setting. The hotel is famous for a painting in the lobby that depicts a woman in rags in one of the rooms; she was one of the many Holocaust survivors housed briefly in the hotel after returning from the horrors of the camps. In the present day, the artist’s granddaughter, memory specialist Dr. Olivia Finn, must quickly head from London to Paris when the hotel calls to say that her grandmother is in the lobby, needing help that she insists only Olivia can provide. Olivia’s grandmother says that she killed a woman at the hotel during those terrible first post-war days; she has dementia, but could her confession be true? Memory and its porousness are central to the plot here. So is the turmoil and moral ambiguity of 1945 Paris: Resistance men who fraternized with Nazis are showered with honors but their women comrades branded “whores,’” while the police work to uncover collaborators attempting to pass as camp survivors. With twists to spare, a fast-moving plot, and piercing looks at what it was like to start over after the war, this is one to get on your TBR list.

Stewart brings us back to a time of tumult: mid-1960s rural Vermont. In this sequel to Agony Hill, we are reintroduced to Detective Frank Warren, a good guy whose efforts at law enforcement—assisted by Trooper “Pinky” Goodrichsend—see the two of them traipsing up and down the county at all hours. This book opens as one of the visitors to the Ridge Club, a hunting and fishing lodge exclusively for rich and distinguished men, is found dead, on the same day that deer season opens. A mere coincidence, right? But Frank suspects that there may be more than someone accidentally shooting themselves while cleaning their rifle. So he and Pinky launch an investigation that tangles them up in the Ridge Club members when a violent snowstorm comes along to isolate them even further. This closed-circle narrative is wonderfully well-done, deeply satisfying, and a compelling portrait of a community undergoing change. Readers who enjoy these books will also appreciate Julia Spencer-Fleming, William Kent Krueger, and Ausma Zehanat Khan.

Chase Burke works as a sommelier for a restaurant in New York’s Chrysler Building and has put his military life behind him. He’s about to ask out a pretty government official, Tanya, who is visiting him on the job, when armed men attack, and she seems to be their target. Chase kills some of the men, but Tanya is hurt. Detective James Campbell and his partner, Detective Alice Doyle, are assigned the case and are told to work closely with Federal authorities. They soon determine that Chase has a lot of skeletons in his closet, and he immediately becomes the prime suspect. Chase realizes he must uncover the truth if he’s not going to rot in jail for the rest of his life, but digging for answers puts him in the crosshairs of a secret group of killers that thinks he knows too much. Whom can he trust while his face is plastered all over every news channel? From the opening page to the last, this book is a relentless force of non-stop action and thrills. Gervais and Steck write great books and have crafted a stellar story together. Comparisons to Mark Greaney and Jack Carr are warranted, but this first in a series might be even better. The next one cannot come fast enough.

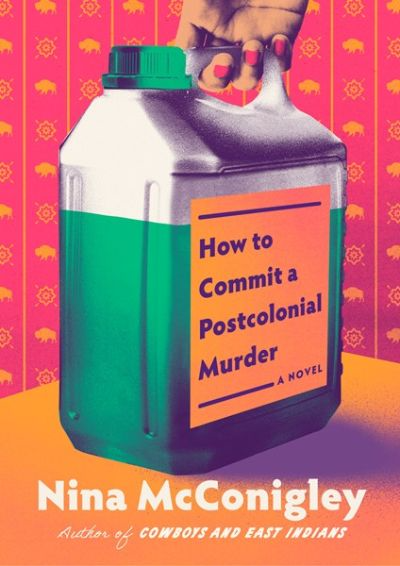

“The Ayyars dipped into our lives like a tea bag into the whiteness of a porcelain cup. They muddied the water and made our house feel small….” In the summer of 1986, tween narrator Georgie Ayyar Creel; her sister, Agatha Krishna; and their amma (mother) welcome newly arrived relatives from India to their cramped home in rural Wyoming. Moving into Agatha Krishna’s bedroom are Vinny Uncle, Amma’s beloved but useless younger brother, whom she has not seen in 14 years since marrying geologist Richard Creel; Auntie Devi, Vinny’s bossy wife; and their son, Narayan. Tensions quickly arise, and so does the sexual abuse when their uncle targets Agatha and then Georgie: “Vinny Uncle made us shadow people.” Forced into silence by their abuser, the sisters decide he must die. The accidental death of a cat provides the murder weapon and sets the siblings’ deadly plot into motion. This highly original debut novel by the author of the award-winning short story collection Cowboys and East Indians is a darkly funny coming-of-age tale with a touch of murder and a haunting twist. Celebrating girlhood and sisterhood in the 1980s, it’s also a touching portrait of Indian-American teens, caught between cultures, in the American West.