A brilliant and moving telling of a Black American family’s struggle to survive despite traumas both old and new. It’s 1981 Detroit, and the Armstead family is celebrating Ozro’s 37th birthday. Treated to lunch by his brother, with a large celebration planned for that night, Ozro heads back to work. Except he never gets there. Ozro disappears, leaving his briefcase and suit coat in his office, abandoning his wife Deborah, his young daughter Trinity, his family and friends. Shifting between the perspectives of Ozro, Deborah, and Trinity, Gray reaches back to Orzo’s time as part of the Great Migration, traveling from the south to Detroit in the 1970s; to his early courtship with Deborah, an aspiring singer; and to Trinity growing up in a world that’s been shattered. Ozro’s disappearance is like the sun, with the other characters as moons, forever circling around it. “I wondered about him all the time because absence was not the same as death,” says Trinity. “It was worse, given all the not knowing.” But it turns out that the mystery of Ozro’s vanishing is only one in a series of traumas that extend from his childhood to his death. Beautifully executed and tremendously poignant, this book is absolutely perfect for reading groups.

Family Life

Yes, it’s only October. But my money is on Bad Summer People as the best beach book of the summer of 2023. Set in Salcombe, a made-up community on Fire Island—not the like the gay Pines, more the reclusive and ritzy Saltaire—this book, in the great literary tradition of Peyton Place, has it all: adultery, fashion, tons of gossip, backbiting, lying, hot sex with the tennis pro, tasteful plastic surgery, alcoholism, and even a corpse. Plus the sort of casual racism and classism liberal one-percenters indulge in. It opens with a prologue, set at the end of August, in which a body is discovered face down off the boardwalk. The book then backs up to late June, as the all-white residents arrive from the Upper East side and Scarsdale for the start of a new season. From there we follow the tumultuous summer in chronological order, moving quite handily among a group of narrators, from the above-mentioned Stanford tennis coach to the Filipino nanny to the gay Yale student/bartender and many more. At the gravitational center of the book are Jen Weinstein and Lauren Parker, the “it moms” who married into Salcombe—their husbands are best friends—and oversee the social action. Not another word from me, lest I spoil any of the fun, except to say the identities of both the victim and the murderer pack quite the punch. This book really hits the sweet spot for popular fiction and will appeal to a broad swathe of readers.

Remember We Need to Talk about Kevin, Lionel Shriver’s dark novel about a mother’s fraught efforts to understand her violent son? Here, neighbors believe Valerie Jacobs has set up her own version of Shriver’s book: her son, Hudson, suspected years ago of a violent crime, is back home and seems eager to live off mom. Valerie’s daughter, Kendra, is against the arrangement. Valerie has always spoiled Hudson, Kendra says between snapping at her mother’s attempts to be a new grandma and pushing miracle cures for Valerie’s seemingly encroaching Alzheimer’s disease. Then a shock crashes into the setup: a young woman is found murdered in the neighborhood and Valerie’s neighbors immediately point the finger at her home. Even Valerie herself suspects Hudson, except when she’s suspecting herself and her memory gaps. Garza (When I Was You) excels at making our heads spin as facts emerge, some from the present and others the past, adding to both the murkiness and the drama. This tale is constructed on a scaffold of slights, family grudges, deceit, and quiet love, all of which build to an out-of-the-blue reveal. This isn’t—thankfully!—as dark as We Need to Talk about Kevin, but it’s every bit as gripping.

Sophocles’ play Antigone, written in 441 BCE, is here pulled into modernity by Burt, a consultant for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The ancient play sees brothers instigate a civil war, and one of their daughters, Antigone, defies her uncle and puts her brother first. So it is in The Dig, which opens amid a civil war, this time in 1993 Sarajevo, Bosnia. Andela, age three, and her brother Mujo, six, are found by American construction-worker brothers in the rubble of a destroyed building, their dead mother nearby. Their Antigone takes place in Thebes, Minnesota, where the children, now called Antonia and Paul, have a “typical American upbringing, blah, blah, no drama,” after being adopted by Eddie King, one of the brothers. Except it’s not really drama free. The blond and hearty residents of Thebes are not ready for the dark-haired, reticent Antonia and Paul, and Eddie dies of an overdose when he can’t handle the new responsibility. What the King family decides for the town is taken as local law, but Antonia defies her Uncle Christopher, graduating from law school and decidedly not working for her family. Paul rebels even more, protesting the Kings’ development of a new shopping area that displaces his Somali immigrant friends and then disappearing. Finding him and getting to the bottom of their pasts, both in Bosnia and more recently, will draw Antonia into a storm of lies and corruption and a fierce battle for control of her life. Feelings when ambition and family collide are no different today than in 411 BCE, and the resulting spectacle is no less captivating.

Ready for a psychological game? Liz Bennett wasn’t, but that’s what her marriage has turned out to be—but is the game a one-sided figment of her imagination, or is her husband, Arno, an adulterer who’s playing her along? The backdrop to the maybe game is deep unhappiness and insecurity on Liz’s part. She and Arno are new parents, and motherhood is more difficult than she imagined. It’s not very enjoyable, with baby Emma looking at her “like she’s an elderly spinster I’m grooming for her banking information,” and no time or energy to write a follow-up to her semi-successful first novel. At least she has Arno, who’s worried about his wife’s happiness and shows love and support for her at every turn—a steadfast situation that she’s terrified to lose after she sees a text to him from an attractive coworker, a message that could signify a romance. Liz is soon spiraling into an abyss of fear and suspicion, one that’s incredible enough to keep readers turning the pages but believable enough to elicit real empathy for this broken soul. Sullivan has a way with characters, using dialog and Liz’s astute, cutting observations to bring Arno, crunchy-granola nanny Kyle, and bitchy-perfect sister-in-law Rose (“I’ve been up since 4 a.m.”) to gossip-worthy life. Fans of women’s fiction will eat this up.

A bold, ambitious, and sprawling work that can only be described as Dickensian, so rich is it in socioeconomic observation, unforgettable characters, sentimentality and violence in equal measure, and, of course, the pleasure of plot. Like any good epic, the novel opens in media res, at a horrific auto crash that kills five homeless people. Behind the Mercedes’ wheel is Ajay, loyal servant to Sunny, an enormously wealthy playboy whose riches protects him from any retribution. But Ajay, of course, wasn’t driving the car, he’s a mere prop positioned to take the fall. How did he end up here? The novel heads back to Ajay at age eight, when he was sold into servitude, his eventual meeting with Sunny in the Punjab mountains, and the move to New Delhi, where he emerges as Sunny’s servant, drug dealer, chef, and bodyguard. Here the narrative jumps to Sunny, still obsessed with his gangster father, whose corruption and violence he wants to transcend while continuously finding himself enmeshed in it. Only his lover Neda, a journalist whose passion for Sunny is outweighed by his immorality, can seemingly reach through to him. As the novel moves among these three characters, all pushed to their very edges, readers are left to wonder whether anyone will escape alive. Brilliant and engrossing, terrifying and heartbreaking, this is one of the best books of the year. Happy to follow these characters anywhere, I can only hope this is the first in a trilogy.

Fraught connections between different worlds hold together this coming-of-age tale: connections between Puerto Rican families in the United States and their homeland; between the past and the present; between the real world and one made of stories. As the book opens, its shy protagonist, Isla Larsen Sanchez, is visiting her mother’s native Puerto Rico. Back in New Jersey, “everyone [looks] so colorless, like the underbelly of a fish,” but at least there she can do her own thing. The island, however, is overflowing with color but also with cheek-pinching aunts who expect proper behavior from a young lady with “not one drop of blood…that is not European.” Over the years, as she spends every summer in Puerto Rico, Isla comes to realize that her oh-so-pure blood may have given her…well, she’s not so sure it’s a gift. She sees visions of tales the cuentistas, storytelling women in her family, have told her—but only after their deaths. When one story involves a murder, and Isla finds that she can be physically hurt by weapons in the visions, readers find themselves dropped into a combination of magical realism, terror, and mystery, all wrapped in a shroud of family secrets and dubious honor. This rich story about stories can work as a crossunder, meaning it can be enjoyed by young adults as well as adult readers; Toni Morrison fans will particularly enjoy the otherworld-tinged drama

Avery lives outside in a tent while her family sleeps inside. Over the years, she’s learned to start her own fires; sometimes it doesn’t work and she’s freezing and hungry, but things aren’t much better for her nine siblings inside. Their parents, cult leaders preparing the family for when they’re the only ones left on Earth, emphasize toughness over all else. The children get their hopes up when the parents announce a buddy system, but it turns out that your buddy is the one who will be punished if you leave, so escape seems unthinkable. Avery finds a way out, though, accompanied by her little brother Cole, only to discover that they’re famous in the outside world as victims of years-ago child abductions. What happened the night the pair escaped and how they will navigate notoriety and society’s expectations are mysteries that will keep readers rapt. Also engrossing are the overwhelming emotions involved with both staying and going, the realization that just because the biggest problem is over doesn’t mean everything is rosy, and the ways tormented people treat one another even when survival is no longer at stake. Avery has grit and attitude to spare and will stay with readers long after the last page.

Bath, England strangers Priyanka, Stephanie, and Jess each receive the same letter telling them that their husbands together raped a woman decades before, with the letter writer, Holly, claiming to be the daughter of one of the men. The women think that confronting their husbands will be the end of the story. (That’s if they decide it’s true and if they can bring themselves to tell the men that they know about the rape, neither of which they find a given at all.) The husbands, too, think their troubles are over. They’re still members of the same upmarket social club where Holly says the crime took place, and still lead fine lives, unlike the victim and her daughter, with the mother now dead and the daughter near death from alcoholism. As the women meet one another and move from emotional paralysis to action, we’re brought to what seems like a definitive showdown. But it’s not the end at all. Ray’s U.S. debut reminds readers, through her storytelling and her portrayal of the women’s undulating emotions, that sometimes what we think will be the end might not even be the most significant part of the story; these women make their own ending, and it includes a startling closing twist. The sadness of lives destroyed is palpable here, but so is the healing force of friendship, not to mention determination. Psychological thriller fans who enjoy strong women characters should add this to their reading plans.

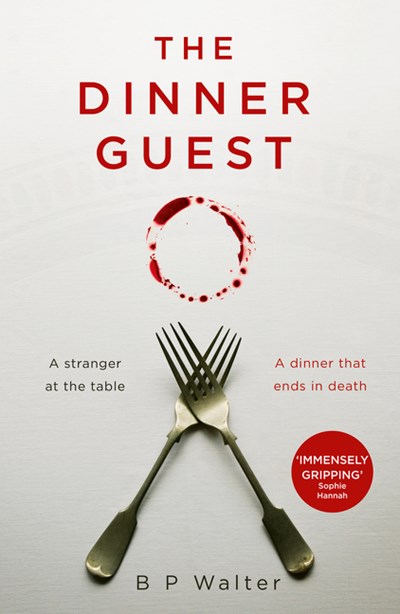

I’m hard pressed to recall a crime novel with a more despicable group of characters yet a more compelling premise. Matthew and his husband, Charlie, lead the perfect life. Rich, well-connected, with a fabulous London flat, access to a wonderful country home, and an absolutely charming tween son, Titus, adopted by the couple after the death of Matthew’s sister. But slowly, things start to fray. Nearly always, the problems stem from Rachel, a stranger the couple met in a bookstore and whom Matthew befriended against Charlie’s instincts. Matthew invites Rachel to join their book group, giving her a wedge that she could drive into their personal life. So when the police are called and arrive to find Matthew at the dinner table stabbed to death, Charlie in shock, and Rachel holding the murder weapon—this isn’t a spoiler, trust me—we aren’t exactly surprised. What is shocking is the complex but gripping backstory that gets us to this point. This novel is very, very British. Class issues abound, class signifiers—schools, stores, real estate, and the like—are everywhere, and some things inevitably get lost in translation. But one thing remains certain: this plot will leave you twisted, and quite a bit disturbed.