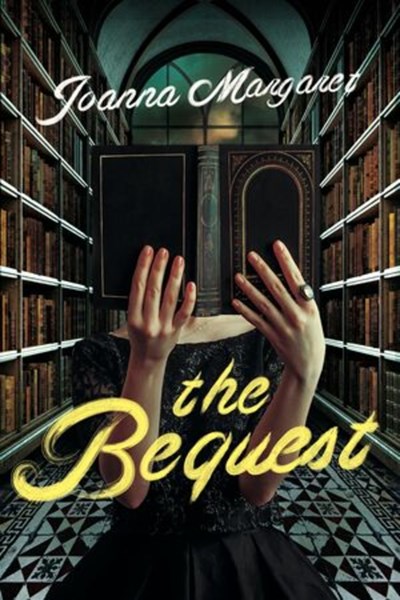

Isabel Henley leaves Boston for the remote coastal Scotland college of St. Stephens, ready to immerse herself in a feminist perspective of Catherine de Medici’s court. She’s chosen St. Stephens so she can work with Professor Madeleine Grainger, but arrives to find that Madeleine has fallen from cliffs near the school and died. There are whispers that it wasn’t an accident, but Isabel hopes they’re just drama—St. Stephens is quite the gossip hothouse. Isabel’s other contact, Rose Brewster, a student she knew in Boston, soon disappears mysteriously, leaving Isabel both socially bereft and unsure of her future at the school. Then things take a turn, both for the better and the much worse. Isabel takes over Rose’s dissertation—it’s funded!—and she’s off to Genoa, Italy, to research the history of a family still living there, the decidedly odd Falcones. Isabel is locked into their home’s archive every day by the debonair son of the house, deciphering letters written during the Renaissance that offer a tantalizing look at past life and politics (a Falcone was involved in a conspiracy to assassinate French king Henry III) and a chance to save Rose. Also tantalizing is Margaret’s language, which immerses us in Genoa’s “intestinal alleys” and Renaissance passive aggression (“I know I can expect nothing in return except for your contempt” is a winning line in one love letter). There are two attractions here: the present-day academic whodunit and the olden puzzle revealed in Renaissance letters; viewers of the Netflix series “The Chair” will eat this up, as will readers of Philippa Gregory and Robert J. Lloyd.

217

previous post

Sometimes People Die

next post